By Gauri Mangala

Features Editor

On Dec. 26, the NY Times published a front-page article about the West-Windsor Plainsboro school district in Plainsboro, New Jersey. The article illustrated the debate of how the students were “overstressed” and the policy changes that administrators have created to lessen the tension. Kyle Spencer featured not only the debate of what schools could do to fix this, but also analyzed the apparent racial barrier between Asians and Whites. In the following article, the Playwickian continues to analyze the debate of WWP, along with connecting it to the strifes of self-proclaimed stressed students of Neshaminy.

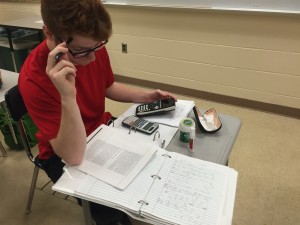

Meet Patrick McCormick. As a high-achieving junior at Neshaminy, McCormick is a busy student. In class, he works hard to maintain straight A’s in 4 AP classes. So far, his hard work has paid off, as he is ranked 6th in his class. Out of class, McCormick maintains a busy schedule between lacrosse, track, Mathletes, Science Club, World Affairs club, National Honor Society and community service, while also balancing extensive homework. With a schedule like this, it is inevitable that McCormick would be stressed. The question is, however, is stress a bad thing?

“Everyone that tries to succeed in school is stressed to an extent, and the only reason I do so much is to go to the college of my choice,” McCormick said. “I do what I can not to let it stress me too much, but it can definitely get to me sometimes.”

McCormick’s story is similar to that of many students at Neshaminy. College is too close. High school resumes are too important. Days are too short. High-achieving students tend to push themselves as much as possible to meet their end goals. And yes, along the way, they will meet stress.

Merriam-Webster defines stress as “a state of mental tension and worry caused by problems in your life, work, etc.”, however, the reality of stress is much more complicated than that. Stress, in healthy doses, can actually be beneficial in getting work done and staying motivated.

In an article entitled “Researchers find out why some stress is good for you” on news.berkeley.edu, Robert Sanders writes that “While too little stress can lead to boredom and depression, too much can cause anxiety and poor health. The right amount of acute stress, however, tunes up the brain and improves performance and health.”

It is finding this healthy balance that proves to be a challenge. Some schools, like West Windsor Plainsboro High School (WWP), have been trying to find this balance. But, unlike other schools, WWP caught the attention of the New York Times in the process.

Making front page news on the Dec. 26 edition of the NY Times, Kyle Spencer wrote that “This fall, David Aderhold, the superintendent of high-achieving school district near Princeton, N.J., sent parents an alarming 16-page letter.” The gist of this letter was that the students were over stressed and changes needed to be made.

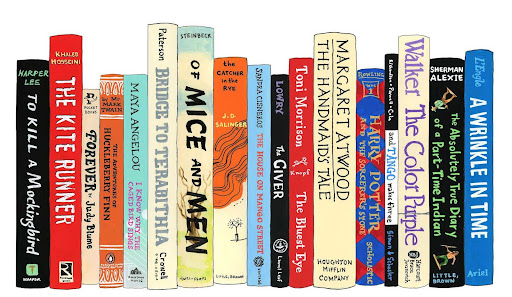

These changes, including the installation of no-homework nights and the cancellation of midterms and finals, have been situated into the district’s academic policies in the hopes of lessening the stress of the students.

WWP has developed a reputation as, as Spencer put it, a “high-achieving” school district. The district pumps out Ivy-League-and-MIT-bound students, bearing 2400 SAT scores, killer resumes and astronomical GPAs. However, as Spencer pointed out, “In the previous school year, 120 middle and high school students were recommended for mental health assessments; 40 were hospitalized.” So yes, the students of WWP are definitely facing stress, perhaps copious amounts of it.

Now, meet Ananya Pappu. A gifted junior at West Windsor Plainsboro, Pappu has much to do. While working hard in AP classes, she also gives her all outside of the classroom. A member of the tennis team, class council, and SAASA- a cultural program at WWP, Pappu also works hard as a dancer of Bharathanatyam- a classical dance from India, a volunteer at a recording center of audiobooks, and a student- working hard at both her SAT prep and her school studies. Pappu’s schedule, much like McCormick’s, is extremely busy, and stressful. However, she, much like McCormick, recognizes the benefits of this stress.

“I feel like we are all stressed, but it’s because we are so academically driven that we are stressed,” Pappu said. “Newspapers have cited that in the past 3 years, 16 students from our district went to MIT, and many more were accepted. The reason our school produces such successful alumni is that the students work hard, and with hard work, stress is inevitable.”

Pappu is correct in her statement that hard work and stress are undeniably linked. Studies show that stress arises when workloads become overly dense, however they also show that stress is helpful in completing tasks quickly and efficiently.

“I, therefore, do not think it is “wrong,” for lack of a better term, for students to be stressed academically. If we reduce the level of stress, I fear students will not work as hard, and our district will no longer produce such successful kids,” Pappu added.

Now, while these new stress-decreasing policies have a great effect on the lives of students, they do also affect another group: teachers. Teachers have curriculums and a clear cut deadline, the end of the year, to get their own work in. Teachers are dependent on homework nights and the looming fear of midterms and finals to keep their students motivated.

In short, teachers must adapt their methods to accommodate these new policies. Some teachers, like WWP math teacher and Neshaminy alum, Charles Ashton, believe that this change has been a long time coming.

“The most simple step – in my opinion – is to reduce the homework,” Ashton said. “We should get more out of class-time with more active student work in the scheduled class hour, and shorter homework assignments in general.” It is Ashton’s belief that it doesn’t make sense to give a ton of homework because, in the end, overloading kids does not make the high school process better for students and teachers, alike.

Empathetic teachers like Ashton have been instrumental in implementing this stress-relieving protocol. “Too many students have unmanageable workloads – leading to sleep deprivation that makes any stress more serious.”

In comparison, many Neshaminy students can attest to sleepless nights due to homework and schedule nightmares. However, most students facing this issue know that what they are doing has a great end result, which keeps them going.

“Individually, I believe that the workloads are fair for the level of the class. I see that everything I’m doing now is going to pay off in the future. I’m planning on taking even harder classes next year,” McCormick said.

It is important to note the vast socio-economic differences between Neshaminy and West Windsor Plainsboro, making it hard to compare the stress levels of students of both.

However, Spencer’s article profiles West Windsor Plainsboro as a new age West Side Story, a battle between strict Asian parents and sympathetic white ones. She argues the existence of a difference of expectations between the two groups. She maintains that Asian parents are against easing up the curriculum, while white parents are all for the change, suggesting that Asian students and their parental units have a stronger work ethic than whites, a common, standardized argument that can not and does not apply to each and every case.

“I think that there is no denying that there is a disparity between the two racial groups, but I don’t think it’s a racial conflict,” observes Pappu. “There are many high-achieving students of all racial backgrounds from my school, not just Asians. Everyone wants to succeed – how can you call that an “Asian mindset”?” Four paragraphs in, Spencer begins to use the word “Asian-Americans” every three to four sentences.

If it were pointed out that McCormick was white and Pappu was Indian, would that change or in any way tarnish either of their achievements as exceptional students? Of course, not.

On Dec. 31, a trilogy of letters to the editor, entitled “Reducing the Stresses Students Face,” was published in response to Spencer’s article. One written by a resident of West Windsor stated that “The high levels of stress – and associated mental problems – are not an issue of race, in my town or anywhere else. Those with a desire to succeed academically do not come in one color.” The letter has been applauded by a number of students in WWP.

To defend Spencer, however, her article was based on observations at a school board meeting, which in no way can accurately depict the emotions of the parents, students, and faculty of the WWP, just like how it cannot for Neshaminy.

Fictional cultural divides aside, parents and schools alike just want what is best for the students. While WWP is attempting to implement stress relieving procedures, Neshaminy is concurrently attempting to establish itself as a strong academically- challenging institution and is adding new AP classes annually.

The second to the before-mentioned letters to the editor stated that while Spencer’s article “seems to [argue] that student academic achievement and healthy personal development are mutually exclusive. Instead, longstanding research, from Jean Piaget to the present, shows that they are mutually reinforcing.” Once again, the argument that stress could be a good thing rings true.

“People will always want to get into the best possible colleges – and need to maximize their grades and scores – and suffer at least some stress in the process,” remarked Ashton. It is in finding this perfect balance of stress and calm that, when produced, culminates into success, and maybe more importantly, happiness.

Stress- an inevitable signal that, in the right doses, tells you that you might just be doing something right. McCormick and Pappu definitely are.

For more information:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/26/nyregion/reforms-to-ease-students-stress-divide-a-new-jersey-school-district.html?_r=0

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/31/opinion/reducing-the-stresses-students-face.html