French voters reject fascism, problems remain

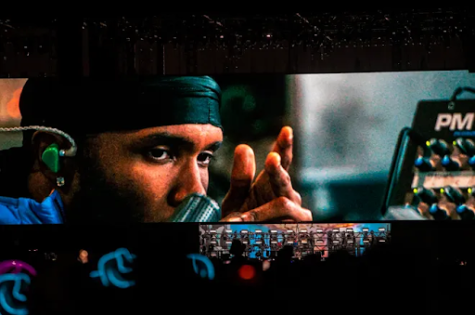

Photo via Google Creative Commons

French President Emmanuel Macron was former banker and bureaucrat before entering the presidential race.

June 15, 2017

The world was watching France when Emmanuel Macron, a senior civil servant and former investment banker turned politician, won the first round of the French presidential elections with 23.9 percent of the vote, beating the far right candidate marine le Pen who came in second with 21.4 percent of the vote.

Macron ran on the En Marche! platform, which he himself created. En Marche! aims to cross traditional party boundaries and be progressive for both the left and right. After the founding of En Marche! Macron said he wanted to “reconcile the two Frances that have been growing apart for too long.”

Political commentators have described Macron’s party as centrist and social-liberal. Le Pen belongs to the far right party founded by her father, known as the Front National.

On May 7, Macron won the presidency with 66.1 percent of the vote. Macron’s overwhelming majority is not a testament to his policies but a pushback against the fascist politics and rhetoric that have dominated the global playing field.

The current French president, François Hollande, congratulated Macron on twitter. “[Macron’s victory] confirms that a very large majority of our fellow citizens wanted to gather around the values of the Republic and mark their attachment to the European Union as a gateway for France to the world,” he tweeted.

Le Pen’s anti-immigrant, racist, and islamophobic rhetoric will not disappear just because she was defeated. France still has a deeply troubling relationship with religious and racial minorities. Algerians and others from former French colonies are still feeling the effects of France’s imperialist rule. Muslims in France are isolated from their non-muslim counterparts and have suffered spikes in hate crimes in recent years.

“You can’t tell generations of kids ‘You don’t belong here’ and be surprised they grow up like they don’t belong here,” Yasser Louati, spokesman for the Collective Against Islamophobia in France said on social media.